“Not to toot my own horn, but I actually did those pictures before Paris is Burning came out,” says the woman I’m speaking to over Zoom. She has thick-rimmed green glasses and straightened dark pink hair, framed by baby pink money pieces. It’s been 24 years since Catherine McGann left The Village Voice newspaper, but you can tell she’s still a punk-rock art school kid at heart.

She has a star-studded 90s portfolio, photographing the likes of Kate Moss, Chloe Sevigny and Leonardo DiCaprio over that decade. Not for stilted Conde Nast covers, but in effortlessly cool black and white party pics and minimalist portraits (it would actually be easier to name the 90s celebrities she didn’t photograph). “I was never interested in being a ‘fashion photographer’, or just shooting happy smiling people with their head in the middle of the frame and all that kind of stuff. I was trying to show more of the scene.”

She graduated in 1986, and went straight to work for New York’s legendary Greenwich Village-based newspaper, The Village Voice.

“After I came out of art school, I really wanted to work for The Voice,” she says. “It was, at least to me, the most cutting-edge publication out there for the visual arts.”

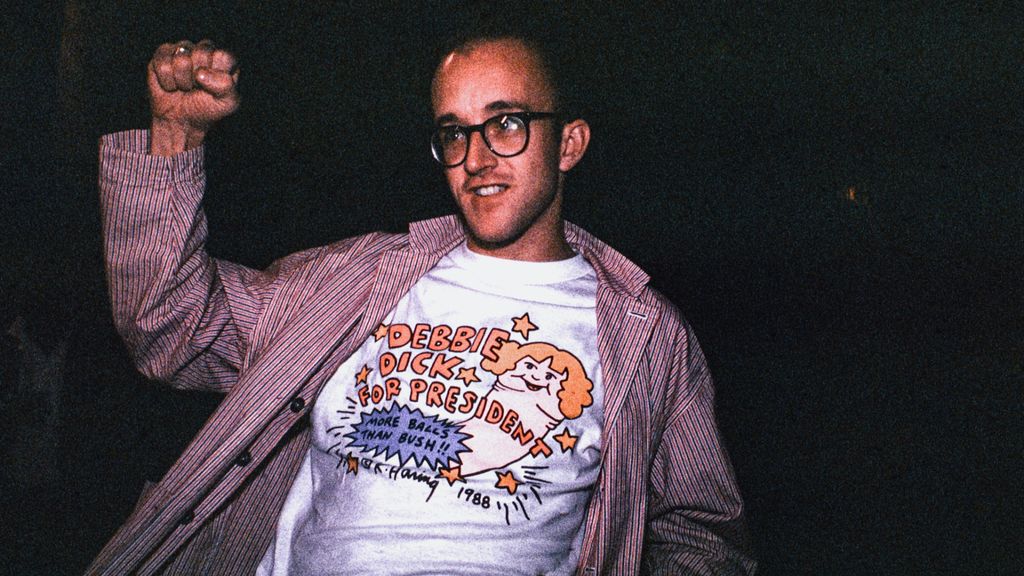

And she got her shot, starting as an intern under “the great” photo editor, Fred McDarrah. Then never left. “It was kind of an extraordinary time, when I look back now. When I first started, there were still people like Andy Warhol and Keith Haring around.”

She soon found herself working with one of the newspaper’s most famous Gay journalists, Michael Musto, on his nightlife column ‘La Dolce Musto’. “My job was to basically do whatever he needed for the column. He loved drag, he loved all kinds of other things that were going on downtown. I worked with him for 16 years on that column. When it started, my photos were the size of a postage stamp, and by the time it ended we were getting double page spreads.”

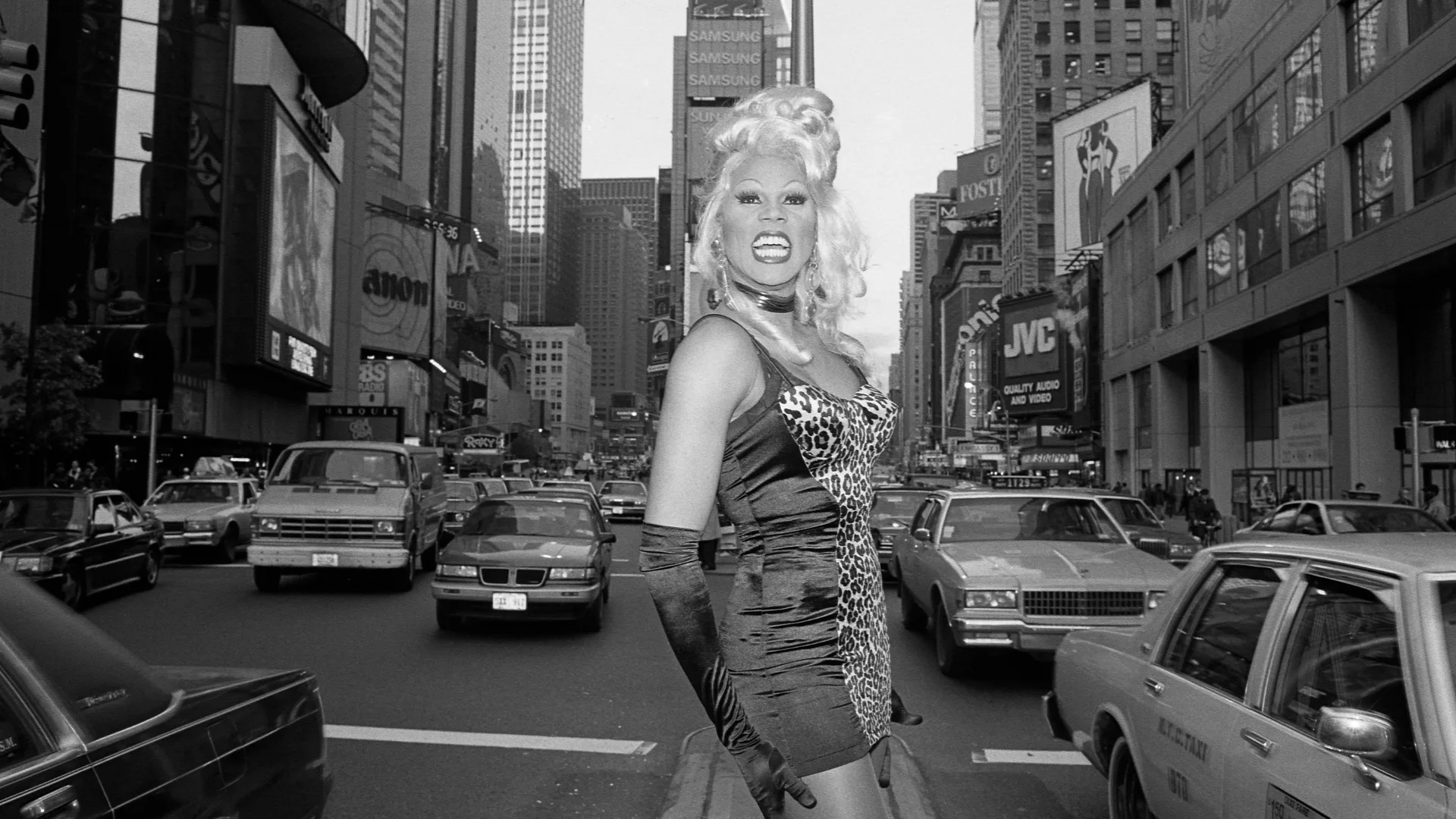

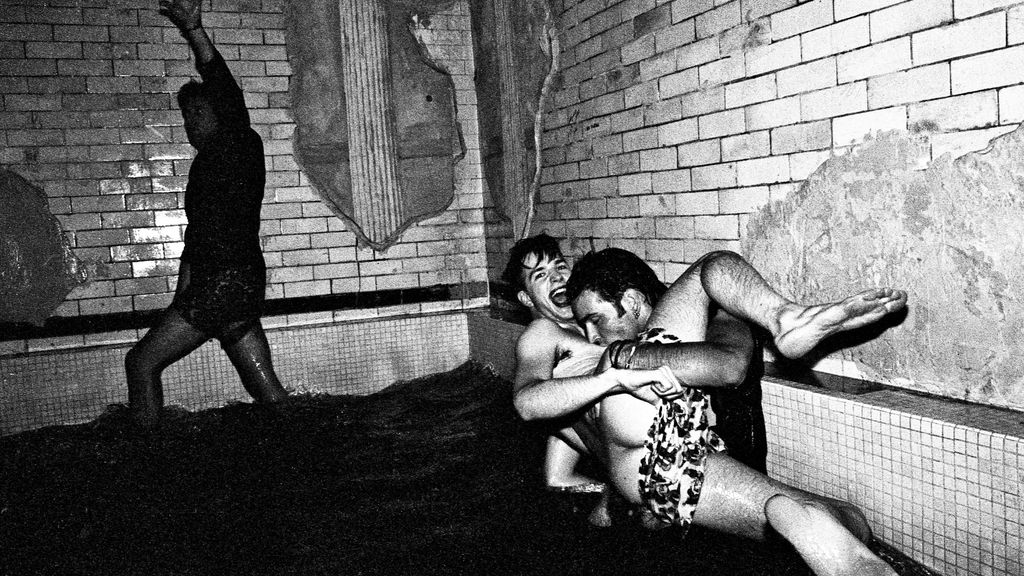

La Dolce Musto brought McGann into New York’s hidden worlds, regularly photographing events at iconic LGBTQ+ venues like Sally’s Hideaway and Club Edelweiss. Musto once summoned her to the Cave Canem former bath house to shoot a party at 4am. She also photographed the rising star RuPaul several times in New York’s drag bars. “And now look where we are! He’s a juggernaut, which is astounding to me.”

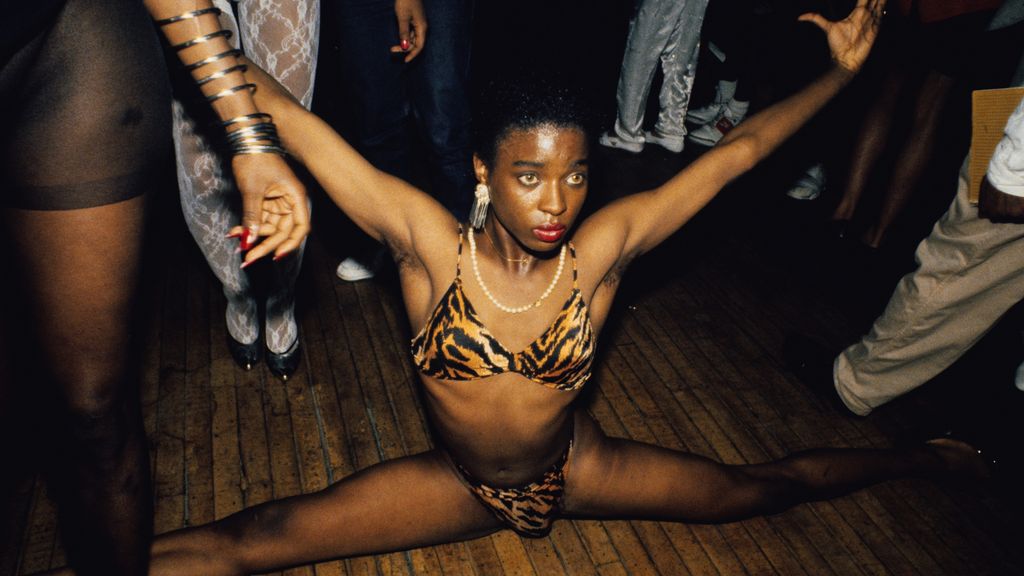

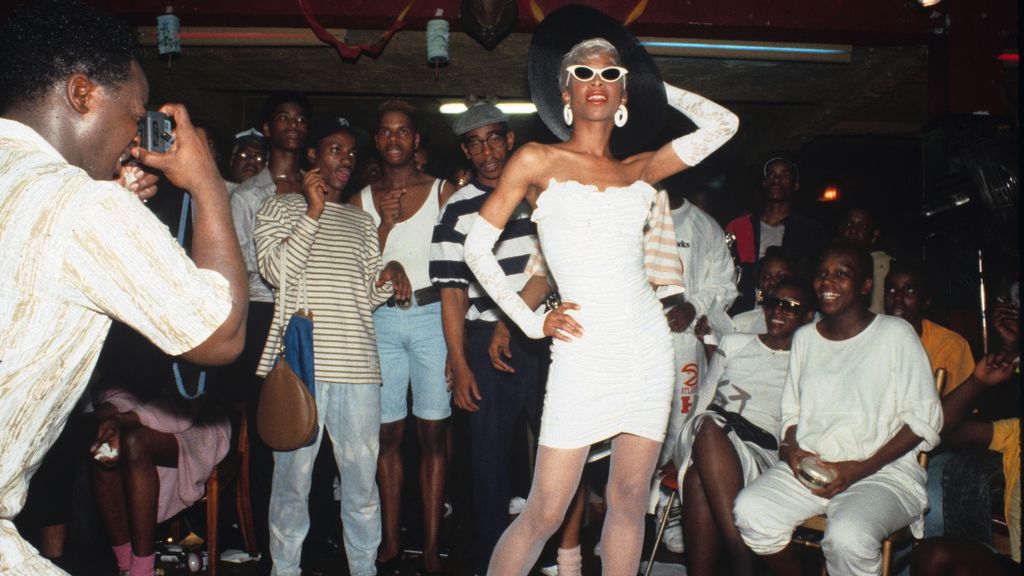

McGann was one of the first photographers to shoot the Harlem drag ball revival in the 1980s, after being invited to accompany legendary Black Gay writer and activist Donald Suggs for a feature. “Now these things seem so mainstream. But it wasn’t then. It really was not.”

I ask McGann to describe the feeling of seeing a drag ball for the first time, before Drag Race and Pose exposed the underground scene to popular culture. “The only thing I can equate it to is that scene in the Wizard of Oz when everything goes into colour. It was just amazing.”

That night she photographed the predominantly Trans, Black and Latino community in the old theatre with style and feeling, recognising them as the superstars they were. “I’ve always seen myself as a big ally and supporter. But here I was, this straight, cisgender white woman with this fabulous, Gay, African American man. But they were very welcoming to me. I feel like I owe them a lot, and many of those girls are gone. Most of them died of AIDS. You feel like you have a responsibility to people for these lives that they lived that were very painful and hidden. And yet I was there with a camera, with a flash – they were very aware of me. I don’t recall anyone really saying no when I asked to take a photo. I’m very grateful that I was allowed that window in.”

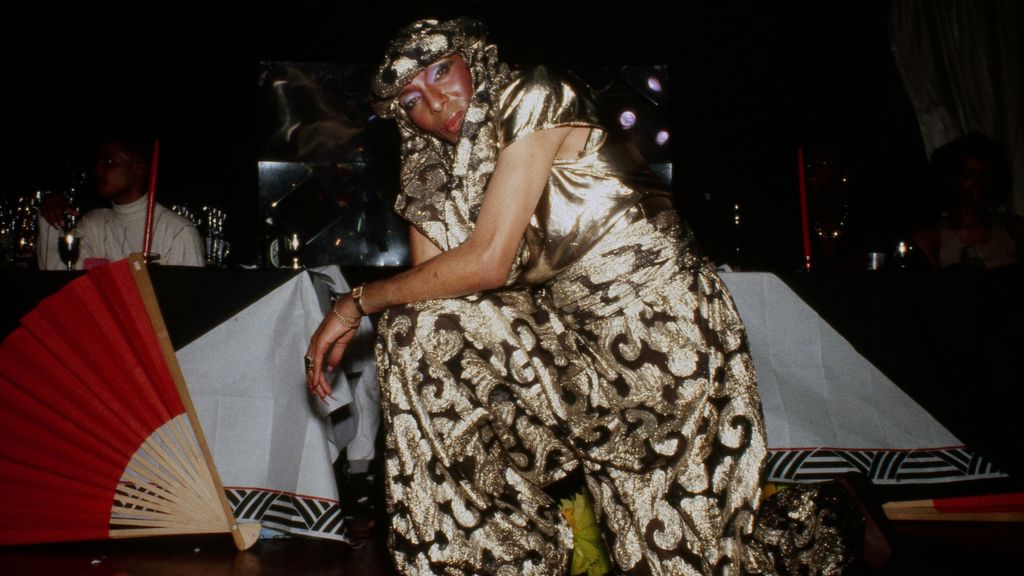

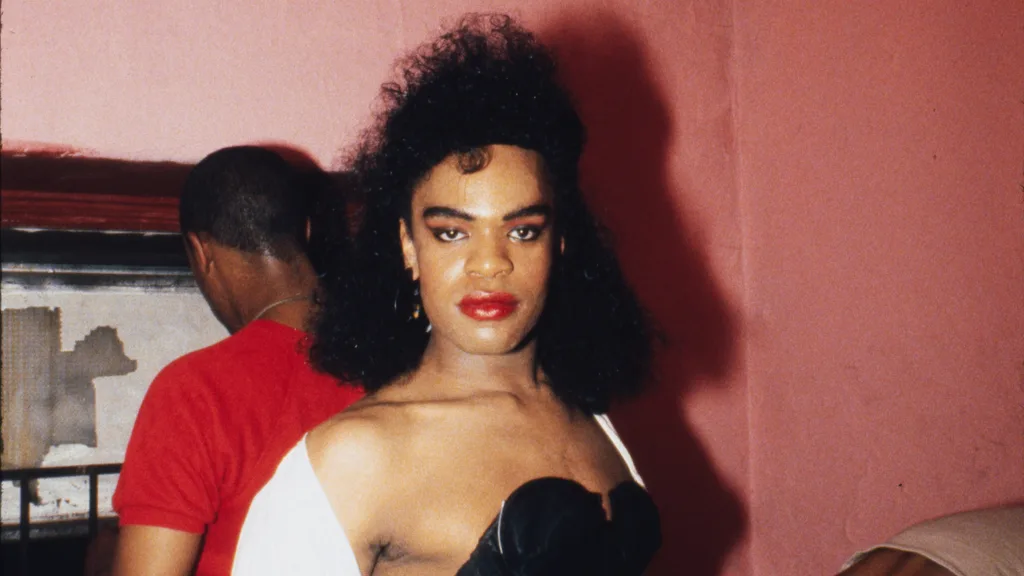

One of the women she photographed that night was the late, great Octavia St Laurent, who instantly attracted McGann’s camera with her beauty and charisma. “I mean, she was just… how fabulous is she? She really was amazing, and everybody there thought so. She really stood out to me. She was very beautiful. She really had it. I also did a fair amount of photos of supermodels on the fashion scene at one point, and she had that kind of energy.”

The comparison would probably fill Octavia with pride – the “voguing” dance style itself was so-named for its mimicry of models pulling exaggerated, elegant poses. “The entire thing really was created for them to have their own fashion show,” says McGann.

She also recalls being “captivated” by a young Carmen Xtravaganza, who stares back from one of Catherine’s photos with big doe eyes and a huge bouffant of black hair and tulle. She fans herself with a piece of paper, bringing to life the sweat of the 1980s Harlem theatre.

She compares it to the flurry of modern voguing events which have cropped up in the wake of Pose and Drag Race’s popularity. “I’m trying to think of a better word than realness… but it was much grittier. It was much more serious. Some of these girls would work on those outfits and their looks and their hair and makeup probably for months in advance. Some of them may have been made by them. It was a very sacred event to that community. And you were either part of it or you weren’t.”

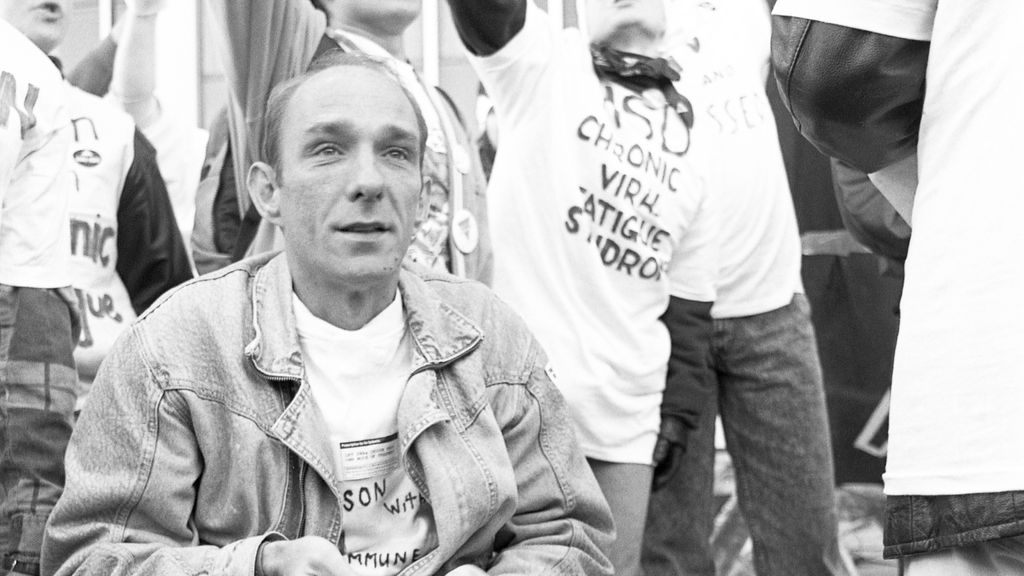

As McGann documented New York’s LGBTQ+ nightlife scene, the AIDS epidemic grew. “When I shot the Harlem Drag Ball in 1988, AIDS was ripping through the Gay community in New York. I was very young when I started there at the paper, in my early 20s. A lot of the people were much older than me, and lived through the 70s nightclub scene. That generation was decimated. I remember the fear and horror of it for the Gay community. Michael, the writer that I worked with, he was very outspoken about AIDS. This was at a time where people still weren’t really even saying it, in the very beginning. Reagan was not doing anything. Nobody was addressing it. He wouldn’t say the word. People were so angry and so many people were dying.”

The sadness grew to anger, as McGann observed through her work. “People were literally fighting for their lives. I look back at some of my photographs and you can see how many of them were already really sick and I’m sure they’re not here anymore. It was a really sobering time and it was frightening in New York, and most especially in the Gay nightlife scene. But I think as we went on, from the late 80s into the 90s, there was a certain nihilism as well for some of those club kids. I remember overhearing conversations with some of my Gay male friends talking about how some of the younger kids were not being as responsible about wearing condoms. I wonder if there was a certain, ‘who cares, let’s just blow everything up, I’m gonna die anyway’ kind of feeling.”

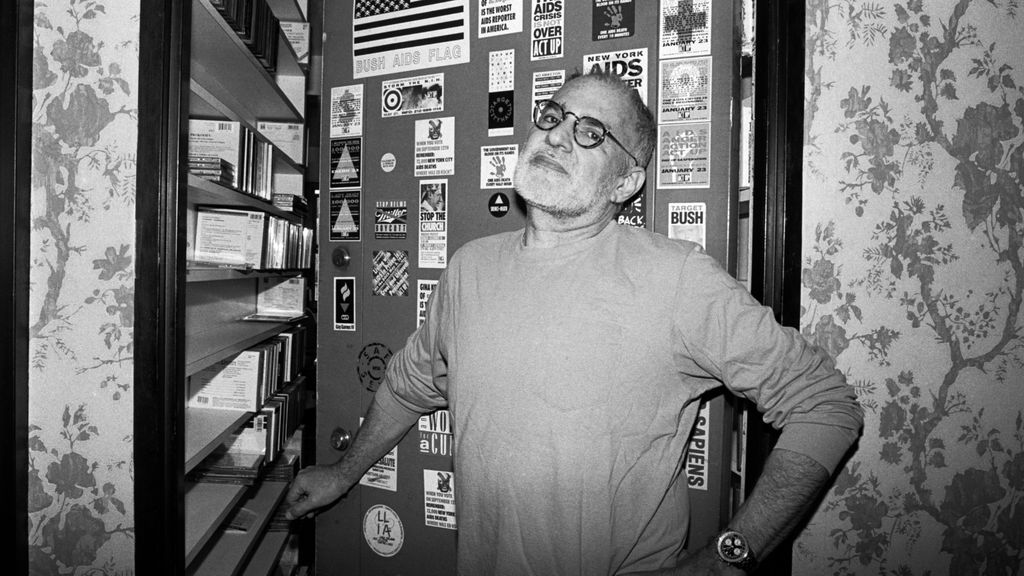

One of McGann’s regular subjects was the writer and co-founder of direct-action AIDS activism group ACT UP, Larry Kramer. “He was really smart, really loud, really cranky and angry, and I loved that. He just got up there and just ripped people apart.”

I ask if the AIDS epidemic naturally made her photography more political over time. “I think it was political from the get-go,” she says. She recalls accompanying ACT UP to Washington DC to photograph a protest outside the FDA.

“I have pictures of people hanging effigies of Reagan. They actually broke the glass and climbed up on top of the building. It’s amazing that I was there as a witness for that. It was very important. I’d like to see a little bit more activism now,” she says, pointedly.

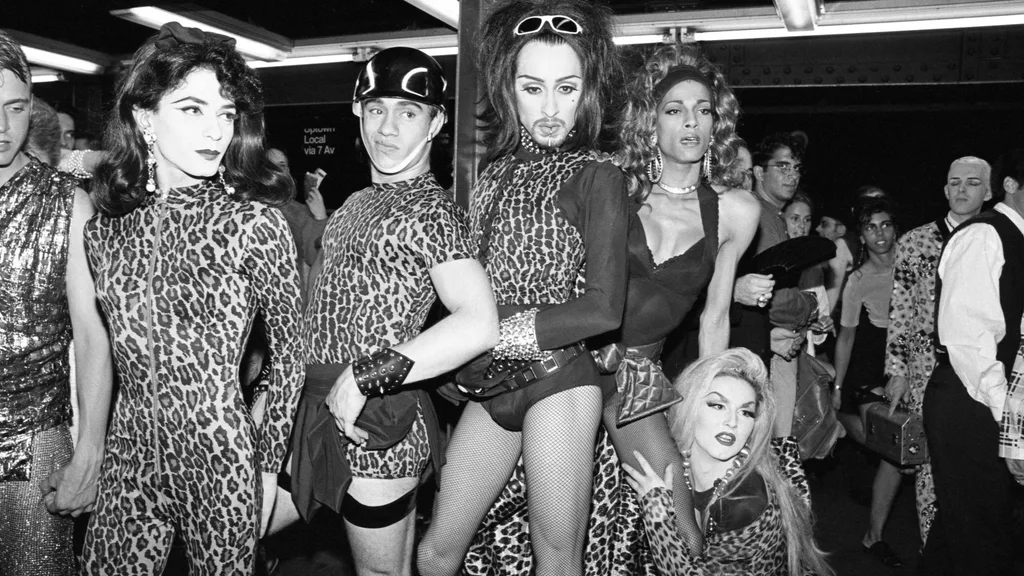

One of the most famous nightlife events shot by McGann was Susanne Bartsch’s Love Balls in 1989 and 1991. The benefit raised $400k (nearly $1m in modern terms) for people living with HIV/AIDS. Combining the Harlem drag ball format with corporate sponsorship, the 1991 Love Ball was a who’s who of Queer celebrities and their allies, with a guestlist that included Madonna, Brooke Shields, Jean Paul Gaultier and Leigh Bowery.

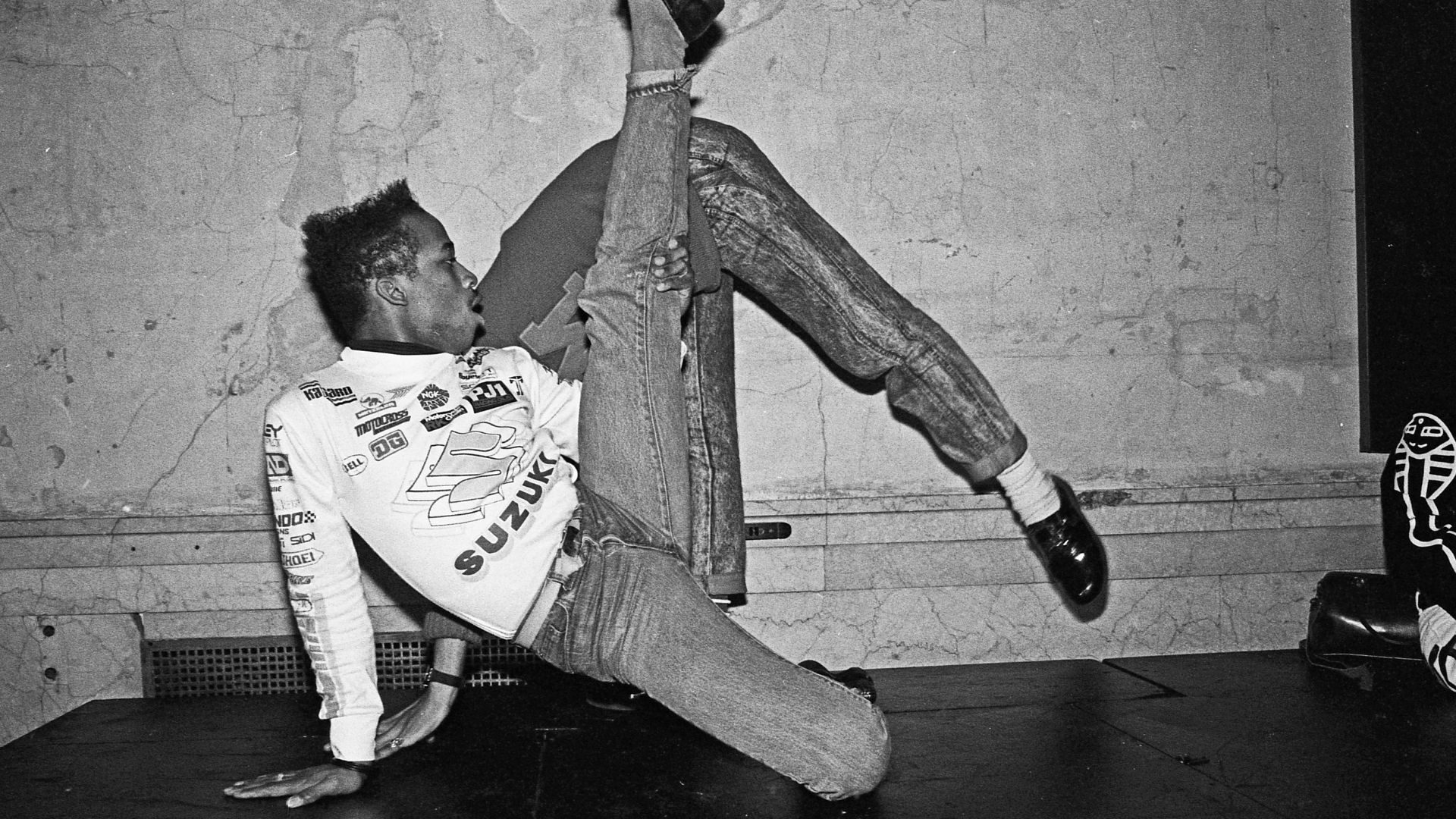

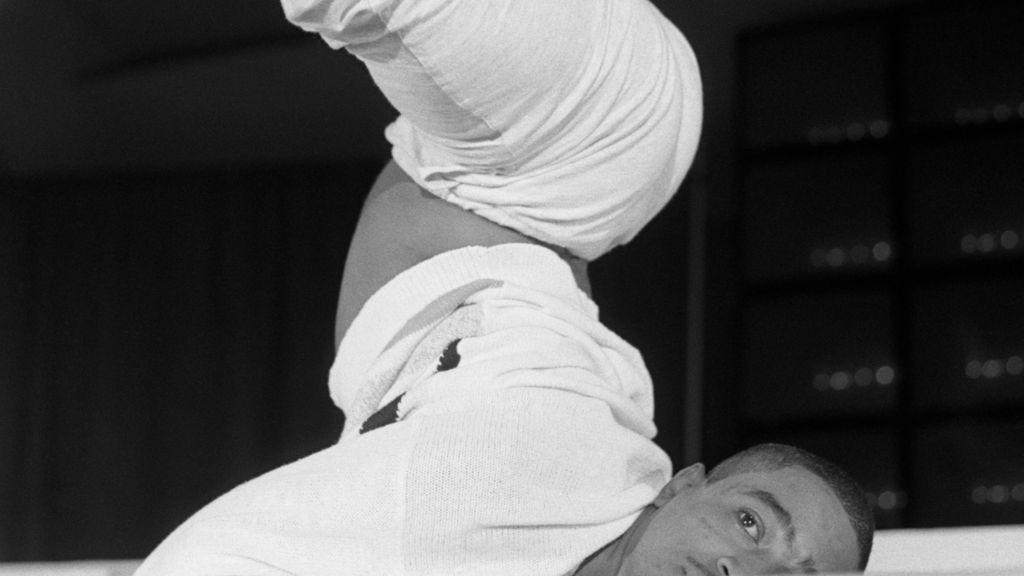

“I wish I’d done a better job!” says McGann modestly, when I ask about her photos from those nights. “It was a crazy night. I think probably my better pictures are the ones of Jose Xtravaganza and him dancing, because I was able to do those in black and white. I shot those right up against the stage. But the chaos of that event, it’s like, should I be here, should I be there. I’m sure there were things that I missed. There were some performers on stage that I wish I’d gotten better photos of.”

I wonder whether the spontaneity and revealing nature of McGann’s New York party photography could ever exist in the modern world of Instagram and TikTok. “You could debate whether there’s ‘truth’ in photography for four hours. But I never saw it as my job to make people look good, per se. I wasn’t particularly trying to make them look bad, either. But I was more interested in a sense of truth… There’s not a whole lot of realness on Instagram. It’s very planned or everything is beautiful, everything is positive… I want to see things as they really are.”

Read more interviews with photographers here.