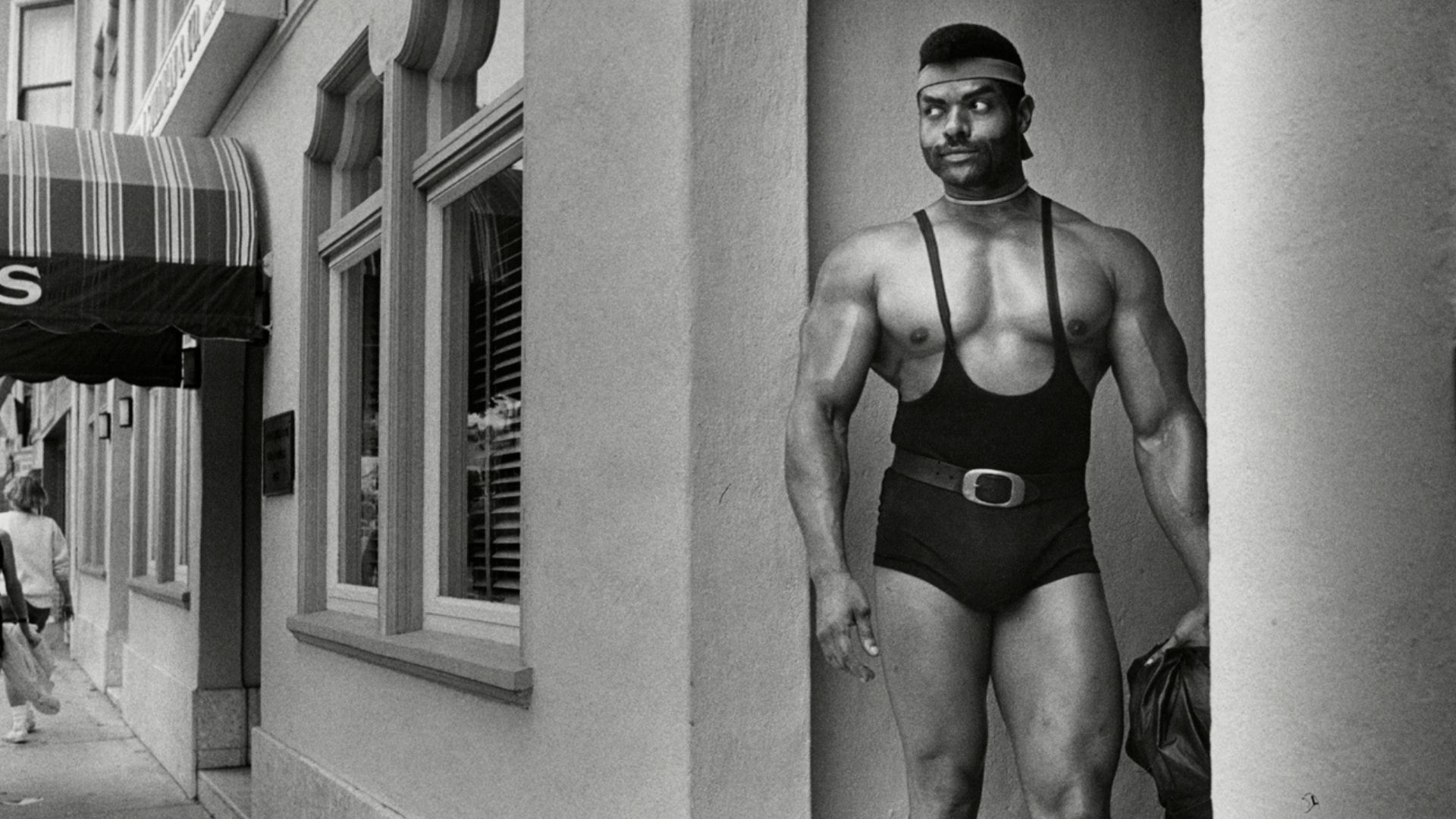

On the streets of San Francisco, California, a man stands on the steps outside a building. He’s looking sideways, chest facing forward. His skin shimmers through black and white shadows, chest gleaming and hairless. The wrestling singlet he’s wearing is microscopic, so low cut as to start below his pectorals, revealing a broad physique. His aesthetic, complete with a sweat band, is very 80s. But it also wouldn’t feel out of place at the Pride events of 2024. But the confidence in his stance, the pride, is what is truly captivating. He is keeping an eye out for those who might keep an eye on him. Maybe he’s cruising, even. Or maybe he just looks fantastic, and knows it.

Photographer couple Saul Bromberger and Sandy Hoover managed to achieve something surprising the day they took that photo – they found a moment of quiet amongst chaos, a furtive glance, the search for Queer connection. Without crowds or rainbows – the whole collection from which this was taken is shot in black and white – it doesn’t look like Pride at all. It would be impressive even for an artist from the LGBTQ+ community to find that energy in a photo. You would never guess from a first glance that Saul and Sandy are in fact allies, who were drawn to capture San Francisco Pride from 1984 – 1990 for their photo essay, PRIDE: Heart Of A Movement.

“We knew back then, and years later, that this would be of historical significance,” Saul tells me from his home in California, about what drew them to the project. “It was to show the love, the intimacy, the sense of community. There were so many nuances. AIDS was starting to become a really huge disease and it was impacting the community. We were just starting to understand what it was all about.”

He speaks passionately about how they saw their role as allies to the community, at a time when that language and position wasn’t as widely understood. “It was just inconceivable to me, to Sandy, at that time and to this day, that there would be discrimination against a group of people. I mean, any group of people, but this group of people. So we’ve always seen ourselves as allies. We know we’re always going to be outsiders.”

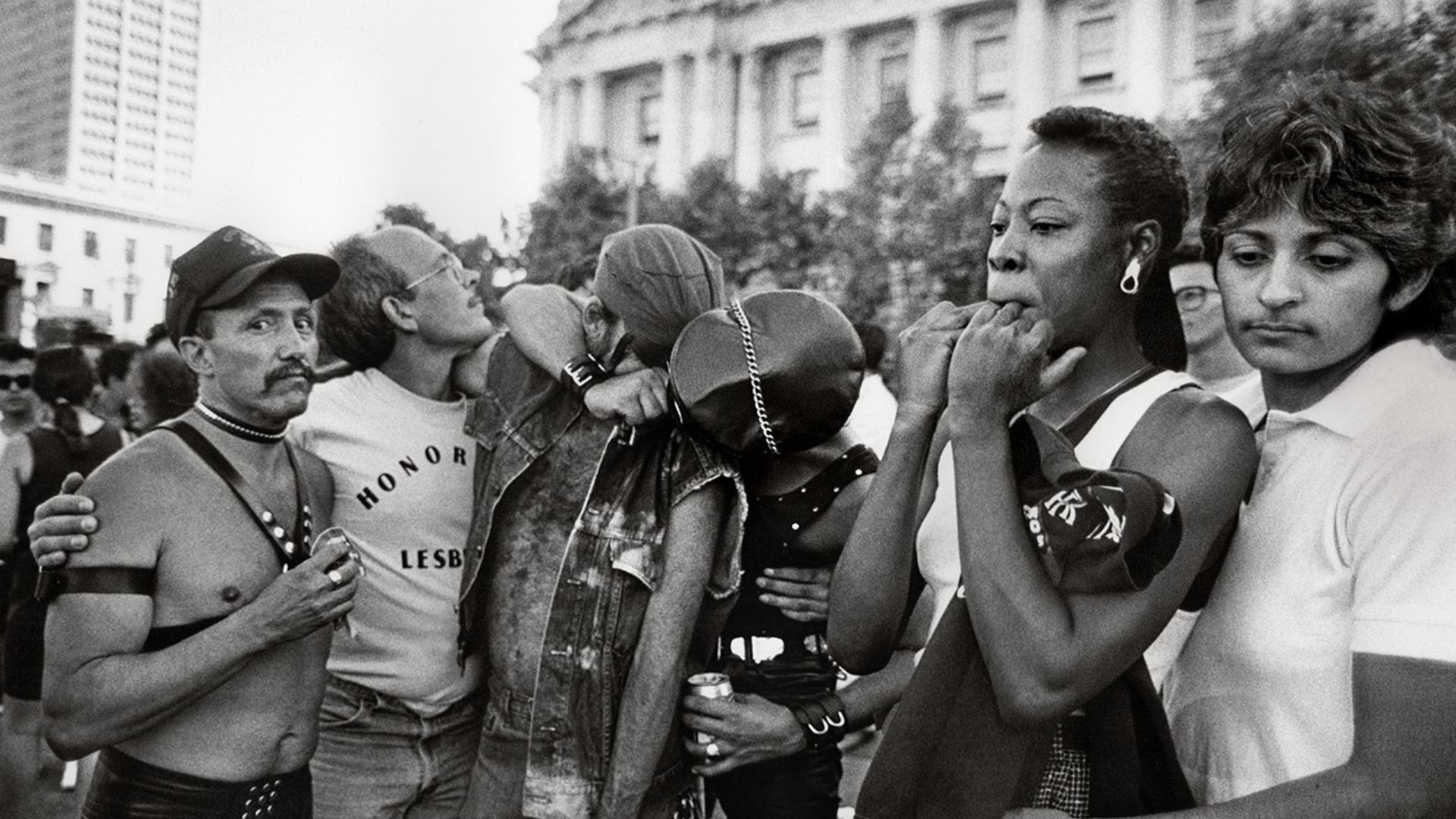

“I was so disappointed and angry,” Saul says of the coverage he saw this year of San Francisco Pride. “They’re focused on the flamboyant, on the extravaganza, on the costumes. Not on the people. Not on their relationships, not on couples. I never saw that. Hardly ever, you know. And that to me was an indication that people didn’t get it… it might as well have been pictures taken at Carnival. It gave no indication of context, journalistic context, that this was about the LGBTQ community celebrating the wins it’s gotten, but also fighting for the fact that some of its rights are being taken away.”

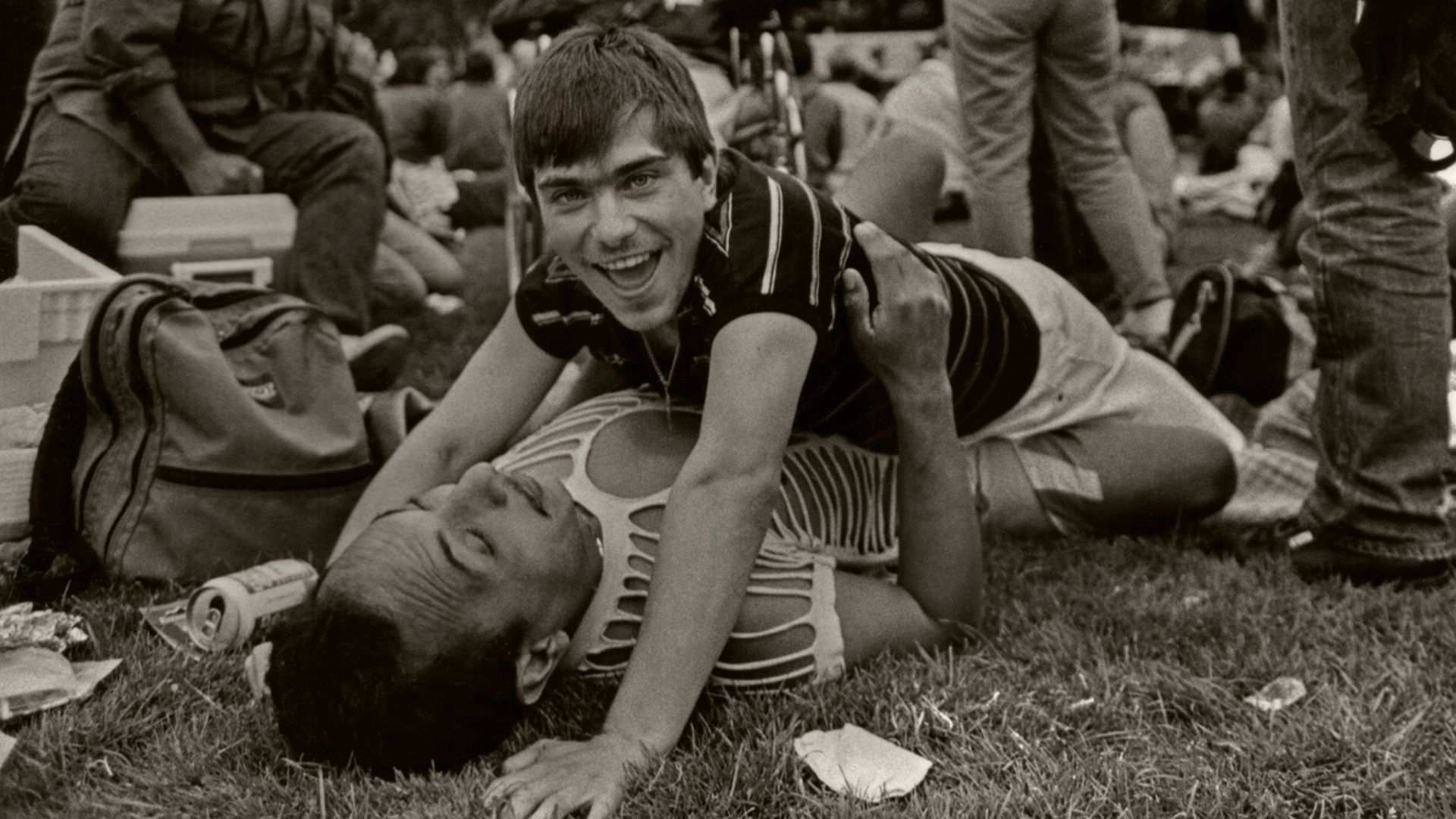

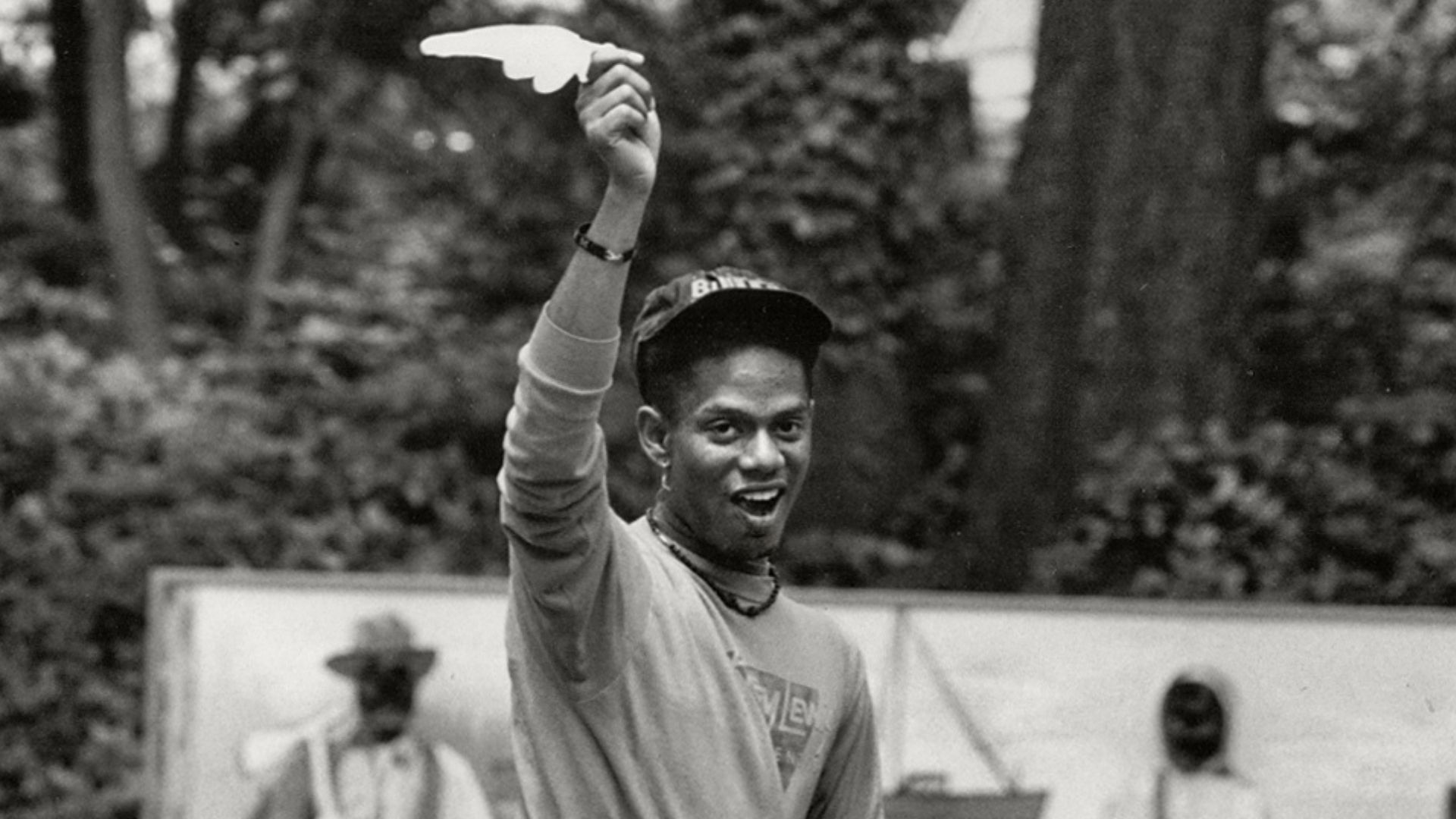

The photos in PRIDE: Heart Of A Movement radiate with the warmth of Queer freedom and friendship. Rather than documenting the event itself, Saul and Sandy capture the laughter that ripples through the air of the day.

Dykes on Bikes wear sunglasses, and sleeveless tees emblazoned with handpainted “Women On The Verge” slogans. They smile with anticipation, waiting to be unleashed on the parade. On San Francisco’s iconic Civic Center Plaza, a man strokes his partner’s beard as he lies down, snoozing. From a birds’ eye view, women in matching white tank tops kiss each other on the grass.

“There was a lot of dancing, and the dancing was just wonderful. We were watching people hanging out, just enjoying themselves. I remember that I was intentionally not assertive. ‘Be cool. Don’t be pushy. Just kind of try to blend in, get your photos’. By blending in we can get these really intimate scenes out. But when you’re doing something like this, you’re getting into people’s spaces, you know, and some people may be uncomfortable with that. So you have to be aware of it, and be respectful.”

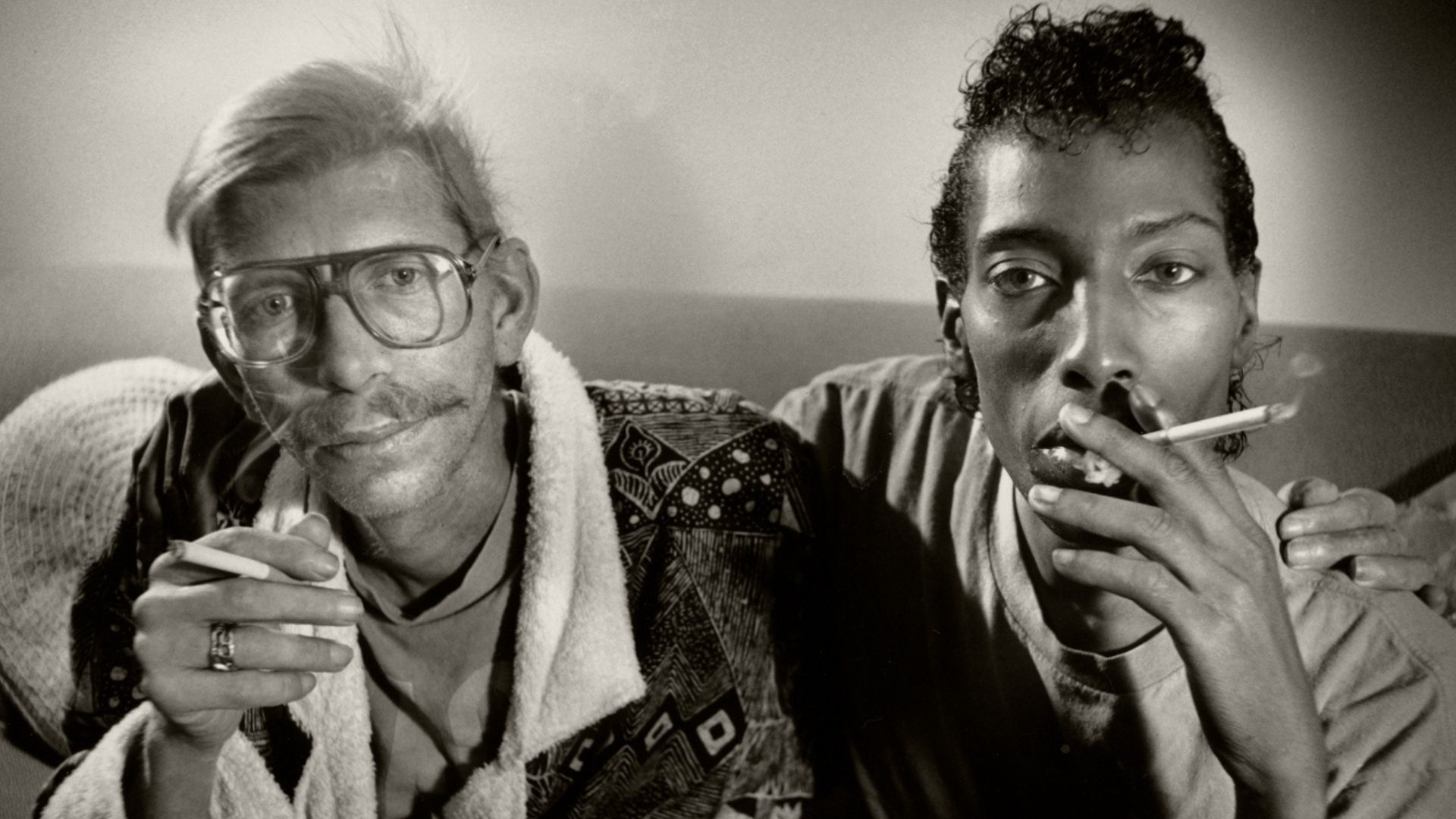

This skill would be pushed to its absolute limit years later, when the pair were invited to shoot portraits of patients at a groundbreaking end-of-life HIV/AIDS clinic in Seattle, Washington. Rather than capitalising on fear of the disease, or allowing the faces of patients to fade into a medical backdrop, House Of Angels – Living With AIDS At The Bailey-Boushay House 1992 – 1995, 1997 is a photo essay showing the resilience, humanity and personhood of its subjects.

Developing a relationship close enough to shoot these intimate portraits took time. “At any one time we had relationships with maybe five to eight families. And because this was a hospice for people living with AIDS, they would pass away. And then we’d meet new people and we’d get to know their families. We got to know the staff and volunteers. We became part of the fabric, the family of this house. People started to trust us. They would tell us, ‘oh, you should meet so-and-so. They have a great family’. And we were seeing some horrific things. We just had to keep our wits about us.”

The centre offered portrait sessions with Saul and Sandy as “photo therapy”, because of the self-esteem boost it gave to patients.

“We wanted to make these people heroic. Beautiful. And to photograph them with the dignity that they deserved. To this day, we can remember everyone’s names.”

One of the subjects was a 29-year-old former model called Carl. “I had already visualised how I wanted this to look. I wanted it to be dramatic and beautiful and warm. So the warm tone here is not by accident. It is intentional. In fact, the whole project has a warm tone. I didn’t want it to be cool.”

I ask what it was like, knowing the photo you were shooting would likely be the last photo ever taken of someone before their passing. “We knew exactly what was happening. And yet when they passed away, it was very hard. Very hard. Every single one of these people eventually did pass away,” Saul says.

But the moments of joy were just as important to capture. “There were some real happy moments here. There were some real moments of joy between people coming together… It was very depressing at times, but not all the time. Not all the time. We sometimes would see a nurse sitting next to a patient, just holding him or helping him to pee into a bucket or some kind of a device. And it was just amazing, you know, seeing what people will do for one another.”

Many of the photos also feature family members, not only caring for their loved ones, but revealing their own terror and devastation. One heartbreaking inclusion is of an 89-year-old mother holding her son, Joel, dressed in a Jewish tallit, tefillin and kippah. “She’s wailing, weeping,” says Saul.

How do you photograph someone in such a moment of vulnerability, in such proximity? “You just accept it and embrace it. The whole idea of being a fly on the wall, that’s not happening… You gotta be socially aware, sensitive to what’s around you, not be too assertive.”

Saul and Sandy pre-scheduled appointments so the photo sessions felt deliberate, and the subjects expected and consented to their presence. “No doubt about it. Video camera, film cameras – Yes, we change, by our presence and by what we’re trying to do, what’s happening. So as photographers trying to tell the story of what’s happening in this house, we embraced it.”

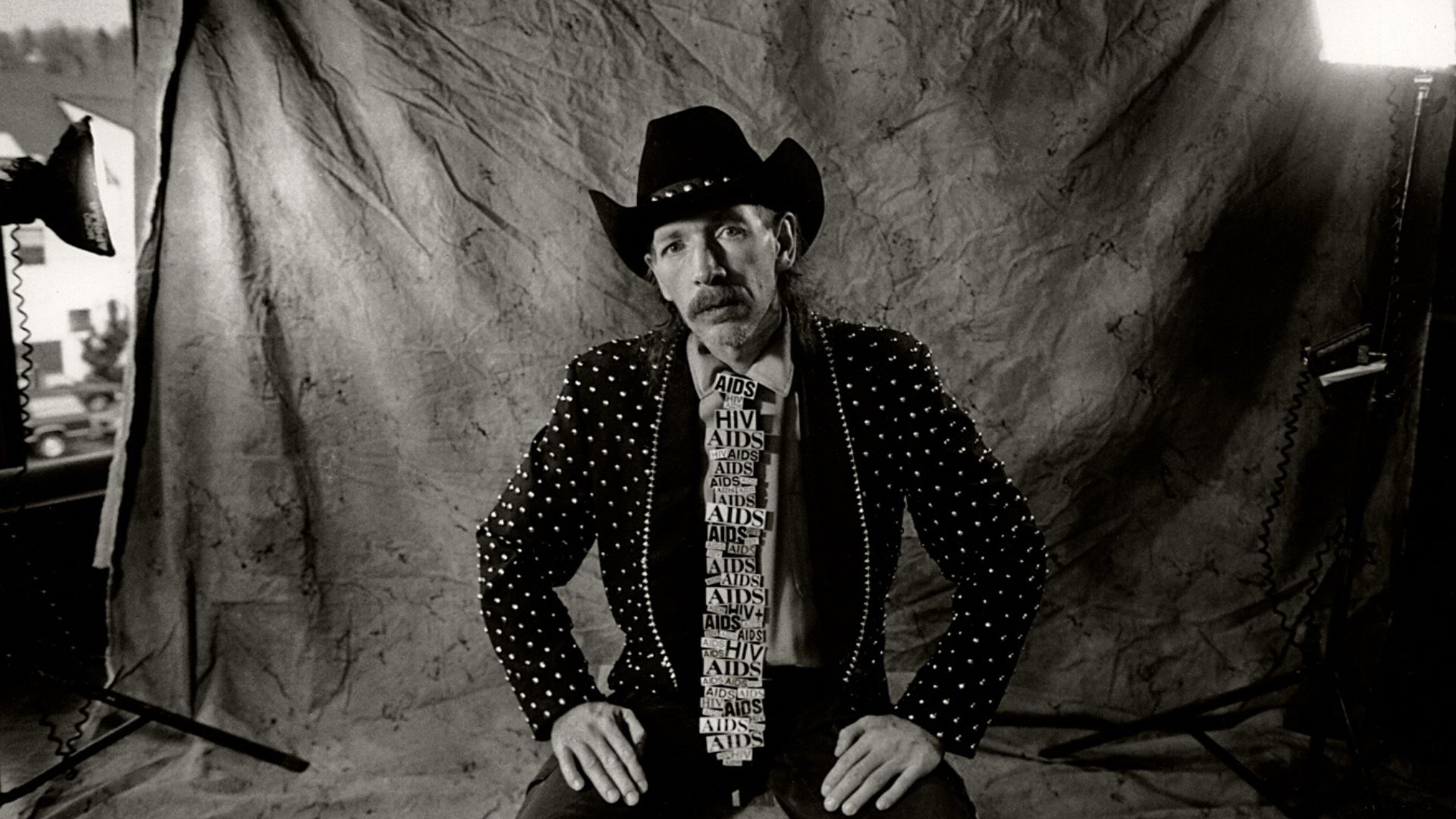

The mirror to this project came around two decades later, when the pair shot Portrait Of The AIDS Generation. They’d put House Of Angels away for around twenty years, not addressing its contents, but started giving talks with it in the early 2010s. They found that some of the attendees of the talks were individuals who had survived the epidemic, living with HIV for many years, trying some of the earliest medications and treatments, which caused other knock-on effects on their health.

“They’re in their 60s and 70s, and they’ve got all of these consequences to all these medications that they’ve taken.” He mentions one such survivor, Hank, who has chronic fatigue syndrome. “It prevents him from doing anything. Basically, he stays in his home, doesn’t get out much and is in constant pain. So that’s when we thought, ‘we need to do a project here.’”

They started attending community meetings and shooting portraits of the individuals they met. “We also worked hard to get women,” says Saul.

In one photo, a defiant woman in a leopard print shirt and matching platform ankle boots stands on a tree trunk, one hand on her hip.

“Her name is Bonnie,” says Saul. “The image here is to show resolve, strength, and sometimes vulnerability. She was scared. She got this from her husband, who had different relationships. She’s not in the LGBTQ community… She loves the people she’s with, but she’s also lost some friends. It brings on a different dynamic.”

I ask what the feelings typically were of people he encountered while shooting the project. Luck? Guilt? Fear?

“They’re in a lot of pain oftentimes. And I think they want people to understand what they’re going through. They want support.”

The work of Saul Bromberger and Sandra Hoover is a testament to how allyship can go beyond watching Drag Race and sharing an infographic. It takes time, effort and craft to not only get to know the LGBTQ+ community as individuals, but reveal the joy, the intimacy, the fight and the fear. From PRIDE: Heart of a Movement, to Portrait of the AIDS Generation, the pair have created a time capsule of the community over time, how it has changed, evolved, and the love that channels throughout. To Saul and Sandy, LGBTQ+ people are the muse.

“It’s just been so enriching to do these projects about the LGBTQ community. So enriching. We just love it,” he says.

You can see more of Saul and Sandra’s photography on their website and Instagram.

Follow the author on Instagram @iamhelenthomas